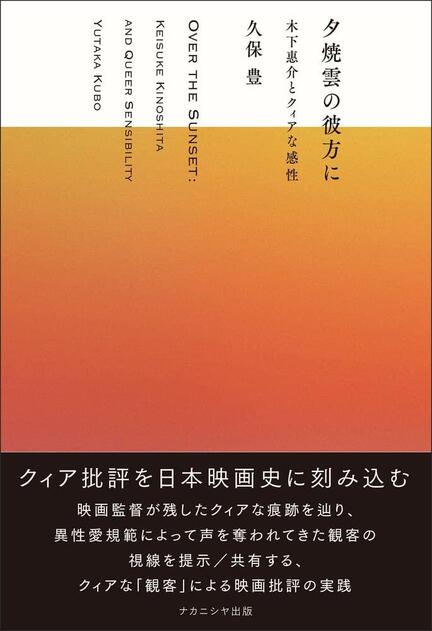

夕焼雲の彼方に 木下惠介とクィアな感性

The present book is a long-awaited contribution to Japanese film studies resulting from its author’s doctoral project. It centers on Japanese filmmaker Kinoshita Keisuke, who was employed at the Shochiku film company from 1933 through 1964.

In this book, the author, Kubo, investigates Kinoshita’s filmmaking practice from the angle of queer film studies. He mainly focuses on one film genre: home movies『我が家の記録(home moveis)』(1939~1949); and six individual films: 『お嬢さん乾杯(Here’s to the Young Lady)』(1949),『カルメン故郷に帰る(Carmen Comes Home)』(1951),『カルメン純情す(Carmen's Pure Love)』(1952),『海の花火(Fireworks over the Sea)』(1951),『夕やけ雲(Farewell to Dream)』(1956),『惜春鳥(Farewell to Spring)』(1959). In this order, Kubo proceeds with his investigation to address Kinoshita’s queer sensibility. The notion of queer sensibility is the idea of weaving into the film text the experiences, emotions, and troubles of people oppressed and restricted by the establishment of heterosexuality as the only ‘normal’ and ‘natural’ possibility of sexuality in modern societies.

Kubo’s aim is not to determine nor identify what elements may help us establish the filmmaker’s sexual identity. Instead, Kubo addresses how Kinoshita’s filmmaking has (intentionally or not) not always been in total adequation with the heteronormative requisites of the Japanese studio system, therefore creating gaps between the expectations about what/how the films portray and what/how they portray it. Through the existence of such cracks, Kubo identifies the possibility of “queer reading”. “Queer reading” is the possibility of actively ‘misreading’ (that is, reading against the consensus) a cultural production (here: a film) against its socio-ideological context. It allows marginalized groups and individuals to get a pleasure otherwise not guaranteed from the cultural text.

Kubo’s analysis is rich and thorough as it integrates numerous sources and angles to convey his argument. First, Kubo compiles numerous historical documents (biographies, interviews, film commentaries, and various footage) to contextualize the films at the center of his research. From there, he uses well-established film studies tools (star image, editing, narration devices) coupled with a thorough textual analysis to provide a compelling analysis of several scenes. Finally, each scene analysis is realized on the backdrop of a solid gender and sexuality theory. Such a theoretical framework posits the hegemonic position of heterosexuality in modern societies and how it has infiltrated every ideological aspect of our daily lives, even our conception of temporality and life course.

This research opus is an unavoidable item for whom desire to conduct research in the field of queer film studies and an excellent methodology guide. Its rigorousness demonstrates how scholars may be capable of simultaneously navigating a large corpus of historical and biographical documents and still providing an in-depth film analysis through concrete narrative and technical devices. Beyond the scope of its vitality for Japanese queer film studies, this research offers a most appreciated rendition of the evolution of the Shochiku film Company through the World War Two period and how the Japanese film industry, through the example of the Shochiku film company, evolved. It shows the variations in film genres, film stars, their images, and primarily how the heteronormative aspects of film production were maintained.

Eventually, starting from the individual film viewing practice of a queer individual, this research explores the elements of queer sensibility in Kinoshita Keisuke’s filmmaking practice. Such queer sensibility can be called upon to re-read Japanese film history and find a place for all the queer lives and experiences invisibilized by the heteronormative anchoring of modern institutions and cultures. Finally, as I turned the last page, Kubo's work, through its overflowing humanity, from the preface to the postface, left a lingering feeling of closeness with the subject, the different personalities mentioned, but above all, to Kubo himself.

本書は、1933年から1964年まで松竹大船撮影所に在籍した木下惠介の映画制作の実践を中心に、クィア映画研究の観点から考察したものである。著者の博士研究に基づくこの書籍の出版を多くの日本映画研究者が待望していただろう。

本書では、クィア映画研究の観点から、木下の映画制作の実践が検証される。木下監督の全作品を網羅的な調査というよりも、主に『我が家の記録』(1939~1949)と名付けられたホームムービーと、『お嬢さん乾杯』(1949)、『カルメン故郷に帰る』(1951)、『カルメン純情す』(1952)、『海の花火』(1951)、『夕やけ雲』(1956)、そして『惜春鳥』(1959)の7作に焦点が当てられている。これらの作品において、木下惠介は、どのようにクィアな感性、つまり、異性愛が「正常」かつ「自然」な性愛の在り方として唯一であるという考えによって抑圧・制限されている人々の経験や感情、悩みを表現しているのだろうか。

著者の目的は、木下惠介の性的アイデンティティを特定することではない。むしろ著者は、木下の映画製作が(意図的であろうとなかろうと)日本の撮影所システムが要求する異性愛規範に必ずしも完全に適合しておらず、それゆえ映画が描くもの/方法についての期待と、実際に描かれているもの/方法との間に亀裂が生じていることを分析の対象にしている。このような亀裂の存在を通して、著者は「クィア・リーディング」の可能性を明らかにする。「クィア・リーディング」は、文化的生産物(ここでは映画)をその社会的・観念的文脈に対して積極的に「誤読」する(つまり、コンセンサスに反して読む)可能性を含む。それによって、周縁化された集団や個人が、文化的なテキストから他の方法では保証されない喜びを得ることができるのである。

著者は研究の中心となる映画の文脈を説明するために、多くの歴史的資料(伝記、インタビュー、映画解説、様々な映像)を収集し、さらに映画研究として確立されたツール(スター・イメージ、演出、ナレーション装置、など)と徹底したテキスト分析を併用することで、いくつかのシーンを説得力ある形で分析している。各シーン分析は、的確なジェンダー・セクシュアリティ理論を背景として実現される。このような理論的枠組みは、現代社会における異性愛のヘゲモニー的位置づけと、それが私たちの日常生活のあらゆるイデオロギー的側面、さらには時間性やライフコースに対する概念にまで浸透していることが分かる。

本書は、映画研究においてクィア理論を扱おうとする者にとって避けて通れないものであり、優れた方法論の手引きとなりうる。特に膨大な歴史的・伝記的資料を操りながら、具体的な物語と技術的装置によって徹底した映画分析を行う厳密さからは、映画研究の新たな可能性が示される。この研究は、日本のクィア映画研究にとって重要であるばかりでなく、日本の映画産業がどのように変化してきたか、より具体的には、第二次世界大戦を通じて松竹大船撮影所がどのように変わったか、を最もよく描き出しているだろう。またそれにより、映画のジャンル、映画スター、そのイメージのバリエーション、そして主に映画製作の異性規範がどのように維持されてきたも示している。

本書を通して行われているのは、クィアな個人の映画鑑賞実践から出発して、最終的に、木下恵介の映画制作実践におけるクィアな感性の要素を探ることである。また本書は、「はじめに」から「あとがき」に至るまで、人間味にあふれた著作であり、それがこの研究を親しみやすく、読者のどこかに響かせうるものにしている。本書が論じる木下惠介のこのようなクィアな感性は、日本映画史を読み直し、近代的制度や文化の異性愛規範の固定化によって不可視化されたあらゆるクィアな生/性と経験の居場所を見つけるために呼び起こすことができるだろう。

(Stockinger Arnaud)